Fujiya Sen-kobo’s third successor explains why the earthen floor, careful technique, and daily discipline remain essential to their work.

Fujiya Sen-kobo began in 1952, during Japan’s postwar rebuilding period. After returning to Asakusa from wartime evacuation in Nagano, the founder established a workshop specializing in the hand-brush technique known as hiki-zome. The second generation later shifted the studio’s main work toward custom Tokyo Yuzen pieces. In 2003, Takatoshi Nakamura stepped in as the third successor, and starting in 2024 the studio also expanded into men’s fashion through collaborations with well-known brands. We asked him to share more about the workshop and family tradition with us.

Your workshop has kept the same earthen floor and many of the same tools for three generations. When visitors enter the space, what is the first thing you want them to understand about its history?

We don’t preserve old things for nostalgia. Everything that remains is here because it is still necessary.

You worked in construction for several years before returning to the family business. What was the main reason you decided to continue the craft after your father retired?

When the first-generation master passed away, my father was just 17; a high school senior. He grew up in a world where “of course you take over the family craft” was a natural expectation, and so he entered the studio.

The reason I chose to continue this tradition is that I realized my role, something that can only be expressed here, truly exists in this place. Our fourth generation, my son, began his training in 2024.

Your father taught you each step of the work with a very patient style. Looking back, what was one basic lesson from him that became especially important after you took over the workshop?

Do the obvious things with unwavering consistency. Even the invisible steps have purpose; skip one, and failure will surely follow.

The importance of the invisible processes is something you only come to understand through failure. A “basic step” you unknowingly skip one day quietly returns as a mistake later. Recognizing the cause-and-effect relationship behind it can be surprisingly difficult.

Which part of the production process requires the most focus from you, and why?

The need for focus begins already in the planning stage. Because we work directly with fabric, I take care of my nails and hands every day. Daily life itself is connected to the work.

Dyeing is a continuous series of instant decisions. The moment dye touches fabric, I must read all the information it gives me and choose the best response. For that, not only skill and experience but a clear and focused mind is essential.

Are there environmental factors, like season, temperature, and humidity that you carefully manage in the studio?

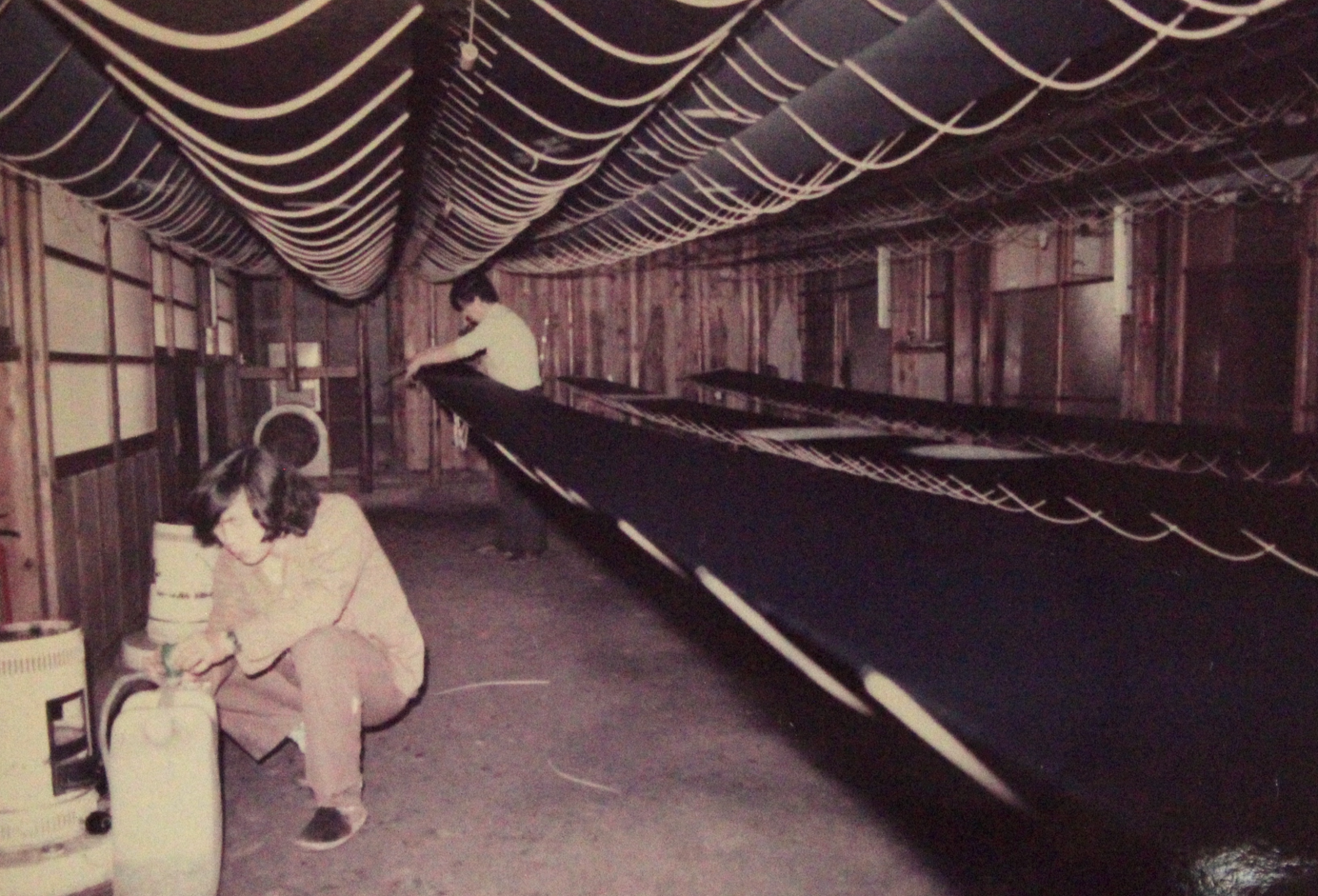

Drying time changes depending on the season, temperature, and humidity, so we constantly adjust the studio environment. We sprinkle water on the earthen floor to raise humidity, use heaters when needed, and hang vinyl curtains to block the wind. In this way, we maintain an ideal dyeing environment throughout the year.

The studio itself influences every aspect of dyeing. This space, and the wisdom to make full use of it, is our greatest inheritance.

You emphasize making practical items that can be used for everyday life instead of focusing only on decoration. Why is this approach important to you today?

We do create decorative works as well; we have produced interior pieces for Hilton Tokyo. But what I value most is giving shape to what customers truly want. By having people use our creations and share their impressions, we can feed those insights back into our techniques and products.

That cycle, I believe, is what allows tradition to continue. Silk reveals its true lightness, moisture retention, and touch only when worn. If someone can feel the story of its maker through the piece in their hands, that brings me great joy.

You also offer experiences for visitors. During studio tours or workshops, what reactions do first-time visitors often have?

Many visitors say they can feel the atmosphere of the studio itself. This space is like a quiet sanctuary where the spirit of craftsmanship lives. The moment color is absorbed into the fabric is truly beautiful.

People are often surprised by my demonstrations, by the movement, and by the finished work.

Some people are interested in learning traditional crafts in Japan but do not know where to start. What kind of student or apprentice is a good fit for this type of work, and what first step would you recommend to them?

Understand the "shuhari" practice; first follow the form, then gradually break away, and eventually cultivate your own sense of beauty.

Looking toward the future, what would you like more people in Japan and overseas to understand about hand-brush dyeing and the work done at your workshop?

The possibilities of dyeing are far broader than people imagine. I want to continue challenging conventions without being limited by precedent. My hope is that my work will become something that elevates the value of Japan itself.

You can follow Fujiya Sen-kobo on their Instagram, and also book an experience at their workshop during your next visit to Tokyo.

Here's a more in-depth video interview with Nakamura-sensei from ONDO Japan:

Know someone we should interview next? Send us a recommendation at hello@bottlecap.jp

This page may contain affiliate links, and Bottlecap may earn a commission at no extra cost to you.

.png)